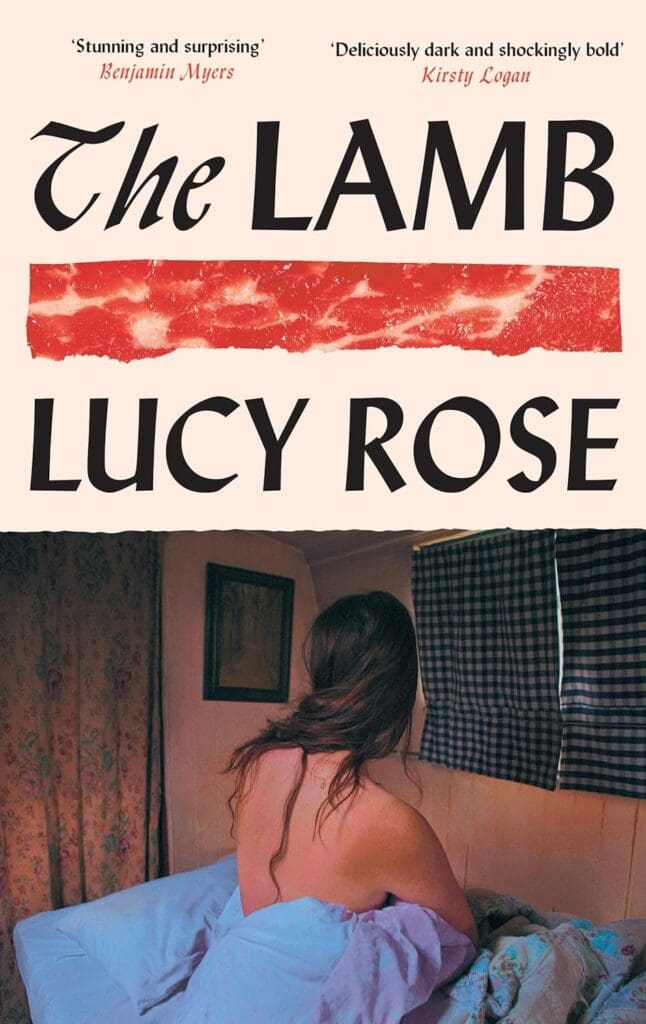

In The Lamb, debut novelist Lucy Rose carves up every last morsel of what comes to mind when you think of nurturing mamas and Sunday roasts.

This is my first experience with femgore, and I’m certainly glad I picked this novel up. A gorgeously grotesque tale of motherhood, desire, and feminine rage, I really enjoyed this debut and I devoured it (sorry) in two days.

Blurb

“Margot and Mama have lived by the forest since Margot can remember. When Margot isn”t at school, they spend quiet days together in their cottage, waiting for strangers to knock on their door. Strays, Mama calls them. Mama loves the strays. She feeds them wine, keeps them warm. Then she satisfies her burning appetite by picking apart their bodies.

But Mama”s want is stronger than her hunger sometimes, and when a white-toothed stray named Eden turns up in the heart of a snowstorm, little Margot must confront the shifting dynamics of her family, untangle her own desires and make a bid for freedom.

With this tender coming-of-age tale, debut novelist Lucy Rose explores how women swallow their anger, desire and animal instincts – and wrings the relationship between mother and daughter until blood drips from it.”

My thoughts on The Lamb

Nature should be feared and admired

Nature plays a major role in The Lamb. Wild and alive, it seems to understand Margot and provide solace in a way people can’t. But while nature can be soft and nurturing, it’s also wholly unpredictable and dangerous, just like the women of this novel.

Lucy Rose captures this perfectly in the character Eden.

Initially, Eden is introduced as a kind, nurturing presence for Margot and a romantic partner for Mama, bringing balance to the intensity and fire of the mother-daughter relationship.

When Margot asks if she is named Eden like the river, Eden replies “Yes, exactly like the River Eden”. That stuck with me as someone who grew up in Carlisle, a city nearby to the events of The Lamb. I remember two occasions where the real River Eden flooded, wreaking havoc upon the city.

I remember once driving down Warwick Road after the floodwaters had retreated, and seeing the grubby tide mark on all the windows facing the street.

It was just before Christmas, and lining the road were skips brimming with sodden carpets, soggy wrapping paper, children’s toys, rotten sofas, and damp Christmas trees. It was heartbreaking, and an unforgettable reminder that we can’t control nature.

The first time the River Eden flooded (in my memory), my friend’s house was spared. The second time my friend lost her home because, after the first disaster, Carlisle council installed flood barriers that shielded one part of the city but ended up forcing the water elsewhere. What saved one neighbourhood doomed another.

I’ve no idea if Rose knew this when she named Eden or wrote the previously mentioned line, but I thought the council’s futile attempt to control a powerful force perfectly supported the core message around womanhood: women can be soft and serene in one breath and volatile and destructive in the next. Does that make them bad? Does that make them less feminine?

No, it makes them human. In summary, Eden is beautiful on the surface, but she harbours the potential to drown everything in her path.

Motherhood

If you want a sanitised exploration of motherhood, kindly put this book down and hop onto Instagram. Rose explores the real, contradictory truth of it as she gives us a version that’s not selfless, but angry and resentful.

Through the eyes of eleven-year-old Margot, we see Mama’s hunger grow all the more insatiable as Margot grows older, becomes more complex and, therefore, more difficult to love (as Mama puts it). The ever-growing hole in Mama’s stomach represents how little is left of women once their children begin to grow into separate people.

I wondered if we were born with something broken inside us. Maybe it was in the deepest marrow of our bones, some place we couldn’t see or touch. Maybe that’s why we couldn’t love each other the way we were supposed to.

Margot, The Lamb

The maternal bond and the family home becomes a literal site of consumption. This is where The Lamb becomes most brilliant. It doesn’t simply say motherhood is monstrous—I’m a mother and I love being one—what it does say is that when society offers women no room for complexity beyond being a mother, the role can eat them alive and hollow them from the inside out.

Femininity, desire, and the “perfect victim”

Lucy Rose takes this one step further as zhe dives into the female experience. Through the eyes of eleven-year-old Margot, Rose covers the horror that is puberty, of hunger both literal and metaphorical, and of the narrow path between being palatable and powerful women are forced to walk within.

While Margot is our narrator, Mama is the central force of the novel.

She’s everything we’re told a woman shouldn’t be. Mama is manipulative, insatiable, sexual, and unmotherly. She weaponises her femininity to control others. She doesn’t fit into a nice neat box of ‘perfect victim’ or ‘complete villain’, because she is both and neither.

This is the central message of the book: women are just people. We’re not saintly, pretty things to look at. We can be as dark as we are light, and live both of those truths at the same time, an idea which Lucy Rose pushes to the absolute extreme.

Rose never condemns Mama, she complicates her. This is especially bold in a culture absolutely obsessed with the “perfect victim”. Because, after all, if a woman isn’t perfect then her suffering doesn’t count/matter.

Margot has her own growing hungers as she navigates puberty. She yearns for love, understanding, belonging, and safety, and she became a threat to Mama and Eden’s happy little bubble.

I loved Margot. I haven’t rooted for a character like this in a long while, and I found solace in the little pockets of safety Rose gave Margot in the form of school and the bus. I just wanted to give Margot the biggest hug.

What I loved and where it faltered

Lucy Rose’s prose is stunning. There is a stifling sense of dread permeating every page, which Rose builds upon until the very last page. While I saw the ending coming, it still haunts me. Yes, Margot deserved a happy ending, but I do think Rose followed this novel to its logical conclusion given the tone and the expectations of literary horror fiction.

I also loved the Cumbrian setting, which is where I’m from. It rarely gets a mention in modern fiction, which I’ve never understood as the Lake District is so unbelievably beautiful and fairytale-like, so it was nice to read a book set there. It’s also heartwarming to see a fellow Cumbrian doing so well.

Despite this novel’s brilliance, I did think it lulled slightly in the middle. The plot temporarily lost momentum as it circles and then re-circles its themes a little too long, and some readers might lose interest during this stretch. Still, the final act is more than worth your patience.

Final verdict on The Lamb

The Lamb by Lucy Rose is a stunning and grotesque tale of motherhood and feminine rage.

You should read this book if you’ve ever felt guilty for wanting too much or hating yourself because you don’t fit in the nice, neat box like society tells you to.

★★★★☆

Rating: 4/5

I’ve read her debut, and now I’m hungry for more (sorry, I couldn’t resist) from Lucy Rose. Really looking forward to her second novel!

Leave a Reply

Recent entries

Be the first to comment